on this day: Rose Island Fires on the French Fleet in the Revolutionary War

Written by Michael Simpson

“As night fell the mortar battery that had been established on Rose Island threw some bombs at us; only one overshot us, which caused M. d’Estaing to give the signal to the closest ships to fire on these batteries. After half an hour, the fire ceased on both sides.”

- French Naval Journal, [Aug 08 1778]¹

On August 8, 1778, cannon fire erupted from Rose Island, marking one of the earliest direct engagements between the British Army and the French Navy in the American Revolutionary War. Though brief and often overlooked, this moment signaled the opening shots of the Battle of Rhode Island and a turning point in the war, one that now included the powerful French military fighting alongside the American cause.

That summer, allied Franco-American were planning to oust the British from Newport, where they had occupied Aquidneck Island since 1776. French Vice Admiral Comte d’Estaing arrived off the coast of Rhode Island in late July, bringing with him twelve ships, a powerful naval presence to support American commanders like Major General John Sullivan, Nathanael Greene, and the Marquis de Lafayette retake the island. British forces on Aquidneck Island braced for attack, frantically building and reinforcing batteries, including one unfinished fort on Rose Island.

In a letter to General Washington on July 24, General Sullivan noted British activity at Rose Island:

“They are fortifying Brenton’s Point and Rose Island, strengthening Fort Island, and repairing the North Battery… all is confusion.” ²

By August 8, the French fleet set sail into Newport Harbor, forcing the entrance of Narragansett Bay in their full battle formation. According to the journal of the French frigate Engageante:

“When the Languedoc had doubled Brenton Point, the batteries that were within range fired on it, but it did not respond to them until it was within range to make it as efficacious as possible, all the ships of the line imitated it, at length their fire was so lively and it followed that in an instant the batteries were dismounted and abandoned by the enemy; the ships of the line in firing in the same regard at the fort that was built on [Goat] Island and some batteries that fired on them from Rose Island and from solid land; the vessels that the enemy had sunk in front of the city prevented bringing broadside on against them.” ³

Although the battery on Rose Island was unfinished, French accounts confirm it did engage the French fleet. Another French journal later recorded the engagement:

“As night fell the mortar battery that had been established on Rose Island threw some bombs at us; only one overshot us, which caused M. d’Estaing to give the signal to the closest ships to fire on these batteries. After half an hour, the fire ceased on both sides.” ⁴

From the British side, the engagement was equally as intense. Captain Frederick Mackenzie of the British Army described the cannonade as “prodigious”:

“About 3 o’Clock, the French Admiral, Count D’Estaing, in the Languedoc, came within shot of Brenton’s Point battery, when the action began. The fire… was kept up with great briskness, and returned by a heavy fire from the ships as they passed… and from those on Goat Island, & the North Battery. … The fire from the Batteries and the ships was prodigious, and formed a very grand Scene… The cannonade continued without any intermission for an hour and a quarter.” ⁵

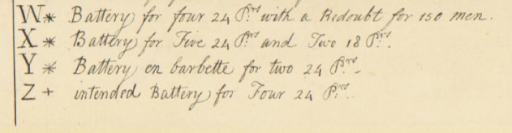

British engineer Abraham d’Aubant’s 1778 map of the island labeled Rose Island with a “Z,” designating it as the site of a planned battery for four 24-pounder cannons. Sullivan received intelligence just weeks earlier that construction was underway. While incomplete, it seems at least one gun was ready to fire, which was enough to elicit a French counterattack.⁶

“It appears certain that they have sunk between Goat and Rose Islands eleven transport ships and several rather large ships, but the channel there is very large & very deep.The one between the point of dumpling, & Rose Island is free, & easy, & the ships of the line can at your choice pursue their route north, or turn to the east, on the battery close to Newport. … It is feared that the obstruction of the channel between Rose & Goat Island does not permit your ships of the line to take the position in which they would be able to take the enemy works.” ⁷

The cannon fire from Rose Island, whether from a completed battery or a hastily mounted gun, may well represent one of the first direct combat between British and French forces in the American Revolution. French officers confirmed they were shelled from Rose Island and nearby land, while Captain John Brisbane, the British naval commander, had sunk multiple ships in the channel between Goat and Rose Islands just days prior to impede enemy approach.

The allied fleet pressed on. By nightfall, French ships had anchored in the harbor, and British forces began retreating and setting fire to their own stores. From the British perspective, in Mackenzie’s journal:

“The burning of the houses and the ship, the sinking of our only remaining frigates, the sight of the enemy’s fleet within the harbor…

formed altogether a very extraordinary Scene.” ⁸

Within days, the French fleet would withdraw following a nor’easter and missed opportunities, and the Battle of Rhode Island would become a bloody stalemate on land. But on the afternoon of August 8, Rose Island, now a quiet refuge, had played a dramatic role in welcoming France to the Revolutionary War with cannonfire.

In the years that followed, Rose Island remained a site of military significance. In 1780, the French army under Louis Tousard constructed an earthwork redoubt on the island. By 1798, the United States began construction on Fort Hamilton, home to the first bombproof barracks in the country. These same rooms, originally designed to withstand cannon fire, were later used by the U.S. Navy to store torpedoes during both World War I and World War II. Today, visitors can book an overnight stay in one of these same historic rooms. And beginning this October, a new exhibit titled Rose Island in Peace and at War will open in an adjoining barracks space, offering an in-depth look at the island’s long history of defense. We hope to see you there!

[1] Hattendorf, John B., Newport, the French Navy and American Independence, (Newport, RI : Redwood Press, 2005), p. 64.

[2] Hoth, David R., ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 16, 1 July–14 September 1778, (Charlottesville, VA : University of Virginia Press, 2006), pp. 158–160.

[3] Crawford, Michael J., ed., Naval documents of the American Revolution, vol. 13, 1 June–15 August 1778, (Washington, DC : Department of the Navy, 2019), pp. 748.

[4] Hattendorf, ibid., p. 64; as cited in Robertson, John K., Revolutionary War Defenses in Rhode Island, (East Providence, RI : RI Publication Society, 2022), p. 50.

[5] Crawford, ibid., pp. 752-753.

[6] d’Aubant, Abraham. Plan of the Town and Environs of Newport, Rhode Island: Exhibiting Its Defenses Formed before the 8th of August 1778 When the French Fleet Engaged and Passed the Batteries… 1779. Map.

[7] Crawford, ibid., pp. 711.

[8] Crawford, ibid., pp. 752-753.